I have written before about the value of having students write as a learning tool. In “Writing to Learn” I made some suggestions for ways you could incorporate writing into you daily lessons. I did not at that time include concrete strategies for helping students actually complete writing assignments. Strategies to help students write in science can improve the quality of their writing and ultimately increase their understanding of difficult concepts.

On August 6th, 2014, I had the opportunity to join a webseminar presented by the NSTA that discussed writing in science. A major theme of this seminar was SCAFFOLDING.

The idea of scaffolding is that you break a task down into more manageable and less frightening steps – at least at first. As students get better at the tasks, then you can remove the training wheels. This article by edutopia has some great ideas for scaffolding.

With writing in science, you don’t want to start with the instructions of “Read this article on cancer and write a summary essay. ” I confess that I did this in the beginning, and then it became apparent that my students had vastly different ideas about what I meant.

Many didn’t understand the assignment just opted out entirely because they didn’t even know how to start.

Scaffolding Writing

Without having a proper term for it, I began to scaffold these writing assignments. Thanks to the NSTA seminar, I have a better idea of the strategies that work for improving student writing, and ultimately, their understanding of complicated science topics.

The first tip I received was related to how you ask your questions. Contextualizing a question can help students focus on what is really being asked. Consider these writing prompts that have been rewritten with context in mind:

Question 1: Explain biogeography.

Rewrite: Why are the animals in Hawaii different from the animals in Jamaica?

Question 2: Explain how speciation can occur.

Rewrite: In Africa, there are 9 subspecies of giraffe, explain how one common ancestor may have split into several different species (or subspecies.)

By offering students a context, they can now focus their writing on specific details. This keeps their writing from becoming too generic or resembling a wiki page with just definitions.

Scaffolding Techniques

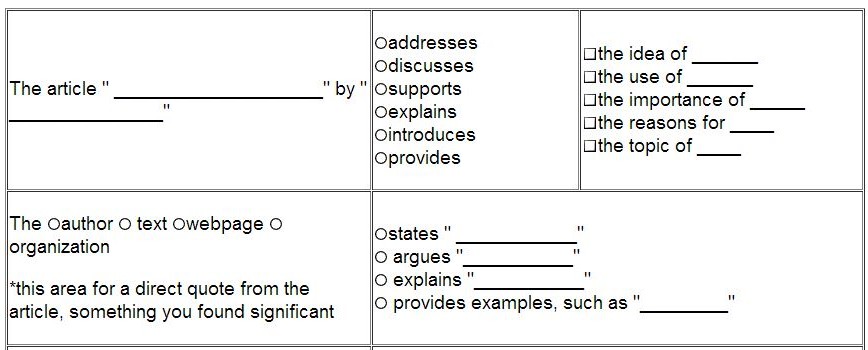

1. Sentence Frames (Framing Guides)

Once you have your writing prompt, consider scaffolding the activity with a sentence frames. I created this framing guide for my AP students to help them with their article of the week assignment.

When your students complain that they don’t know where to start, a framing guide can help them get over that initial hurdle. The frames do not have to be as detailed as the sample above. A simple structure can be effective also, for example: “I disagree with __________ because ________.”

2. Rubrics and Checklists

Rubrics are not a new concept, and I’ve used them for a variety of projects. Give students a rubric that outlines what information you are looking for in the essay. Though, you may want to consider not giving too many details in the rubric which gives too many hints about what you want students to write. They may inadvertently just rewrite the bullets in your rubric. Example of a checklist for an article summary:

1. Establishes context and big idea of the article or the goal of the article ____

2. Includes specific, relevant details from the text of from experience ____

3. Includes personal content, opinions or connections to self ____

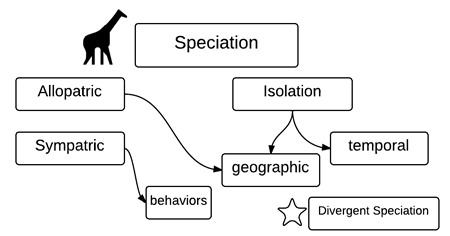

3. Group Discussion

Once the prompt has been given, allow students to work together to create a “gotta have it” chart. If your prompt is about speciation, then students as a group can make a list of importance concepts that should be included in a discussion about the topic. I should not that another theme of the NSTA conference was scientific discourse, and the value of having students talk about concepts and not just sit as passive listeners. In a group, they can come up with things that probably should be included in an essay, but individually, they will have to put those ideas onto the paper and organize their own thoughts. I usually have my groups organize topics with concept maps, like the one shown below.

4. Drawings

If your students really don’t know where to start, have them make a drawing. It doesn’t have to be a fancy drawing. This works great when you are asking students to explain scientific processes, like enzymes and substrates. I also encourage my students to include drawings on their essays and free response assessments on their tests. I also encourage them to annotate their drawings with words so that I know what they are trying to convey. Those annotations usually make it into the written portion.

5. Graphic Organizer

A simple google search for graphic organizers will yield a ton of images that can help students organize an essay. I don’t always use these, but I do keep one posted in my class. The truth is, I don’t have my students write that many formal essays that require a strict format. Most of my writing assignments are informal summaries of labs, activities, or articles or exit tickets that relate to the lesson. Most of my these assignments are intended to be 1-2 paragraphs and explanatory in nature. I want to see what my students know about a topic and encourage more in depth understanding through writing.

If you are just starting to incorporate writing into your lessons, don’t be afraid to stumble at first. Writing used to be something that was just done in english class, but with Common Core and Next Generation Science standards, it’s increasingly apparent that writing something that should be done across the subjects and across curriculum. The more writing they do, the better they will get at it.